Hopi Cycle of the Year

Hopi cycle information gives an overview of the year gathered from many sources and my personal observation and is presented here for your interest and education.

“The complex cycle of interrelated responsibilities and concepts that is the Hopi religious system is all the more complicated because each of the twelve Hopi villages possesses the autonomy to carry out Hopi religious practices independently. The timing of ceremonies, the underlying concepts may vary among the Hopi villages. Nevertheless, throughout the land of the Hopi, the religious mission is the same: to promote and achieve a “unity” of everything in the universe.” (Alph H. Secakuku, Following the Sun and Moon, The Hopi Kachina Tradition)

Hopi rain clouds symbol of life positive energy and abundance

My life has been so enriched by involvement with Hopi friends over the years. I have been blessed to see many of the ceremonials of the year that are open to non-Hopis. The cycles of the year are amplified by these reverent and moving ceremonies. I respect the Hopi right to cultural privacy and understand that many parts of their religious life are only shared with Hopi people and are not open to non-Hopis. These ways have evolved over thousands of years of natured-based living in community here in the Americas. I am very grateful the Hopi people have so faithfully kept them alive and that they are carrying on these ways for all peoples.

If you go up on your own, please check with village offices, the Hopi Tribe or even individual Hopi people who may have shops open, what the rules are for access to the villages. Each village has their own rules about visitors to their villages.

Please respect their privacy and rules.

The activities, dances, and ceremonies are part of a real and living culture and religion and many are not open to non-Hopi people. It is a great privilege that they allow us to come to their lands.

No photography or sketching in the villages is allowed at any time.

Sandra Cosentino

Please read the advice offered about the Hopi cycle of the year to the public by the Hopi Cultural Preservation office below.

“We Hopi are a deeply religious people. We follow divine instructions and prophecies received from the caretaker of this world, Maasaw. Our religion teaches us a lifeway of humility, cooperation, respect and earth stewardship. We practice our religion with different ceremonies throughout the year which are timed according to phases of the moon and solstices of the sun.

Many of our ceremonies seek to maintain and improve our harmony with nature, enhance our prospects for good health and a long, happy life, and are supplications for rain. Through our dances we celebrate the renewal of our life pattern, ancient migrations, and a spiritual connection with our ancestral sites. This, together with our farming tradition, ties us both physically and ceremonially to our ancestral land, the sun and the cycle of the seasons.

Ceremonies are held throughout the year, with the location and date determined according to custom and tradition. Our ceremonial calendar consists of katsina dances from February to July and social or other non-katsina ceremonies for the rest of the year.” (From the official Hopi Tribal website)

Kachina Ceremonials and Visitor Etiquette

Visitor Etiquette from the official Office of Cultural Preservation, Hopi Tribe website

“Katsinam are Hopi spirit messengers who send prayers for rain, bountiful harvests and a prosperous, healthy life for humankind. They are our friends and visitors who bring gifts and food, as well as messages to teach appropriate behavior and the consequences of unacceptable behavior. Katsinam, of which there are over two hundred and fifty different types, represent various beings, from animals to clouds.

During their stay at Hopi, the katsinam appear among Hopi people in physical form, singing and dancing in ceremonies. On Third Mesa the katsinam arrive in December while at the First and Second Mesa they arrive in February at the Bean Dance Ceremony. Night dances are held until the end of March, followed by day dances from May to July. Virtually no weekend goes by during this period without a katsina dance in at least one Hopi village. Most dances start shortly after sunrise (mostly on Saturday and/or Sundays) and continue intermittently throughout the day, with breaks for lunch and rest periods. The ceremonies usually end at dusk. Several of the villages often hold dances on the same day, giving visitors the opportunity to witness parts of several dances by spending a few hours in different villages.

Niman (Home Dance), which takes place in July, is the last katsina dance of the cycle. At the end of this day-long ceremony the katsinam return to their spiritual home at the San Francisco Peaks, Kisiau and Waynemai.

The Katsinam who carry out the religious dances are sacred to us and require specific codes of conduct in their presence. Misinformation about these customs and lack of knowledge about the physical conditions of Hopi plazas were the core of conflicts in the past. While we believe that the Katsinam perform public ceremonies for all people, plants, animals and spirit life, modern conditions make it next to impossible to accommodate all outside visitors. First, there is limited space in the plazas and our rooftops were not constructed to support the weight of hundreds of spectators. Second, sanitation facilities, food, water and emergency services are not designed to serve large crowds. Finally, spectators were originally Hopi villagers and invited guests who were fully aware of the purpose of the ceremonies and how to behave appropriately while attending.

In view of the communities’ difficulties in resolving the issue of restricting attendance at public ceremonies, visitors are asked to be respectful and help monitor the activities of other guests. Through this we can reach mutual respect and understanding. Your participation in establishing harmony will be consistent with the primary purpose of the dances and will be most appreciated by your hosts.”

Hopi Cycle of the Year

November

WUWUCHIM is the first of the three great winter ceremonials portraying the three phases of Creation. This first phase is a supplication for germination of all forms of life on earth, plant, animal and man. The patterns and movements of the stars guide this ceremony.

In the Men’s Societies, the initiated men celebrate this the Fourth World of creation. The fire of life is lit commemorating emergence from he underworld. This is a sacred time of purification and preparation of the prayer feathers and initiation of men as adults into their societies.

Visitors are not allowed in the villages during this time.

December

December in the Hopi cycle is a time of quiet and storytelling which draw lessons from the past to maintain high standards of Hopi life.

The Hopi katsinam (popularly known as Kachinas) are the benevolent spirit beings who live among the Hopi for about half of the year beginning around the time of Winter Solstice with the Soyal ceremony. Kachinas are the inner forms, the spirit forms, of outer life, invoked to assist mankind on their never-ending journey.

1893 Soyal Ceremony

The SOYAL CEREMONY is the second great ceremonial and symbolizes the second phase of Creation at the dawn of life. It accepts and confirms the pattern of life development for the coming year. It is often called Soyalangwul, Establishing Life Anew for All the World. This ceremony helps to turn the sun back toward its summer path and implements the life plan for the year. Activities take place in the kiva and include reverent silence, fasting and humility and eating of sacred foods to achieve spiritual focus. Prayer feathers are placed in homes, villages and around the ancestral homeland in shrine sites.

Second Mesa on winter solstice–notice there are 2 villages on top of sunlit cliffs.

photo by Sandra Cosentino

The prayers and rituals help the Hopi turn the sun toward its summer home and begin giving strength to all life for the growing season ahead. At Soyal time elders pass down stories to children, teaching pivotal lessons like respecting others. The Hopi, The Peaceful Ones (Hopitu Shinumu), believe everything that will occur during the year is arranged at Soyal.

“Woven around this concept are many others that involved the entire community in one respect or another.” Cliff Bahnimptewa points out differences in each of the three mesas in ceremonies conducted and which kachinas appear. Hopi religion is very complex and non-Hopis often tend to overly generalize. Much of this activity occurs within the kivas and Soyal ceremonies are not open to the public.

January

Fall Indian Day Buffalo Dance image

The moisture moon comes in January. Social dances (non-kachina dances) such as the Buffalo Dance are performed by the youth and represent the animals that roam in mountains now covered by snow. The dances are a prayer for snow, for nourishment.

February

POWAMU, the Bean Dance is the most complex of all ceremonies. This is the third of the ceremonies of Creation where life manifests in its full physical forms and growth is consecrated. Many of these ceremonies are not open to the public.

Crow Mother Initiates Children by Ramond Naha

The Powamuya, also called Bean Dance ceremony, is a series of rituals that promotes fertility, germination, and early growth of seeds.

In anticipation of the coming growing season to promote fertility and germination, the initiated males grow beans in the kivas. A fire is kept going day and night to help the beans grow. Patsavu Hu´katsinam regularly inspect the plants. The planting and growth of the beans inside the warm kiva is seen as a good omen for the success of the coming harvest.

On the sixteenth day, the katsinam give away mature bean sprouts in a public ceremony followed by a procession of many katsinam who dance and give away dolls, dancing wands, decorative plaques, bows and arrows, lightning sticks, rattles, and moccasins to the children to honor their good behavior.

Historical and mythological events are given as dramatic presentations. The ogres, guards, whippers appear as disciplinarians, reminders to follow the Hopi way of life.

March

Ösömuya KATSINA NIGHT DANCES

These occur in the underground kivas and are NOT open to the public.

“During this season, the katsinam perform beautiful dances at night in the villages to create a pleasant environment for all life forms so that they will grow and so that rain will come to nourish the crops. The katsinam are always watching and listening for humble prayers and meditations

during the Night Dance season, which lasts from now until some time in July.

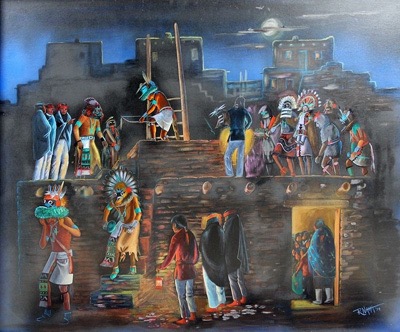

Night Dance at Kiva by Raymond Naha

Angk’wa means “appearance afterwards,” and it is a series of these night dances performed during this period. On a certain night when the people have entered the kiva and are waiting, the katsinam suddenly appear on the roofs of the kiva and announce their arrival with pleasant sounds. The kiva chief invites them in, and they climb down the ladders and give gifts of food like baked sweet corn, that represent the forthcoming crops of summer. They burst into singing and dancing in a prayer for all life forms, then just as suddenly, they stop and leave the kiva and go on to the next kiva, and then a new group arrives. The dance series may go on until just before dawn. It is usually windy and cold. The next day we have a great feast and families visit with each other. Katsinam may appear in the plaza during this time. Then someone, usually

it’s a woman, may sponsor a katsina day dance at a future date to continue the entertainment and spiritual blessings. Such dances are usually scheduled around the planting of crops. Katsina day dances are held from March through June.”

(Ferrell Secakuku, Smithsonian Institute Online)

April

KWIYAMAUYA

The Racer Kachinas appear to bless the people and encourage fitness for short and long distance running. Fields are prepared and the first crop of corn is planted.

“In April, the Hopi start preparing and planting their gardens and fields with various crops, especially corn. Racer katsinam appear in the plaza and challenge men and boys to foot races, thus blessing them with strong and healthy lives. “As the men race, so the water will rush down the arroyos,” the Hopi say. A Mudhead katsina leads the Racers, carrying prizes in a blanket.*

May

Planting time: HAKITONMUYA

“During this period small quantities of beans, pumpkins, gourds, muskmelons and watermelons are planted. The word “haki” means “wait,” as it is not yet the time to plant most of the crops. Katsinam are called upon to help the plants sprout and grow. Many of them represent seeds and different kinds of sacred corn, or blooming plant life; others represent rain, or the increase of game animals. During the early planting season katsina dances are performed on the plaza.”*

June

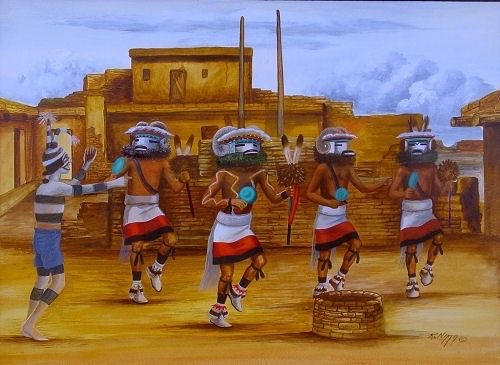

Mountain Sheep Dancers by Raymond Naha

When the weather warms, KACHINA DANCES are held in village plazas (kisonovis). Many of these are NOT open to the public.

Wuko´uyis, the main planting season in early June, is an important time when the first corn is planted and young people and children are taught how to farm. Katsinam appear at sunrise in all twelve Hopi villages and proceed in single file to the plazas. The dances conclude at sunset with prayers and blessings.

July

Talangva is the summer season in July when all the previous katsina rituals and dances culminate in the NIMAN CEREMONY.

“Shortly after the summer solstice, the sixteen-day Niman (or home-going) ceremony celebrates the departure of the katsinam to their spirit world in the San Francisco mountains. After eight days of sacred activities in the kivas, the katsinam perform a public dance. They enter the plaza at sunrise with their arms full of the first green corn stalks of the year, thus demonstrating that corn will be plentiful. They also bring presents, including dolls, for the children. Toward the end of the evening, they reenter the kiva, where an altar has been set up. There they dance for the last time and receive offerings. The father of the katsinam gives a farewell speech, thanking them for past favors and praying for their continued help. He then sprinkles them with corn meal and spreads corn meal on a path for them to follow to the west. The katsinam slowly leave to return to the gods with the Hopi’s gifts and prayers.”*

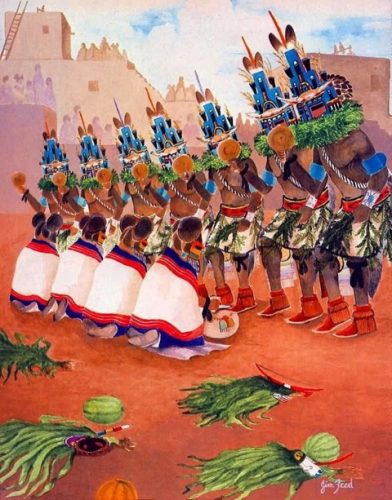

Painting by Jim-Fred: Home Dance Katsinas and the corn grinding maidens, harvest

They may be Mixed Kachina Dances with many different types of kachinas or they may be a dance where all are the same. Feasts are held and neighbors visit one another. There are often clowns to entertain the audience between dances. They bring howls of laughter as they misbehave and show all how not to act.

Kachina plaza dances ending with the Home Dance or NIMAN CEREMONY when the spiritual beings who have been on earth in their physical form return to their spiritual home in the San Francisco Peaks. Brides of the year are presented their robes by their husbands in this last kachina ceremony of the year.

This ceremony acknowledges the powerful forces appealed to during the Soyal and Powamu: germination, heat, moisture and magnetic forces of the air. The first harvest of corn and heaps of food and gifts for the children are all given by the kachinas. These gifts represent bounty of harvest, and great virtues of life for all mankind.

The day after the Nimankatsina dance, eagles that have been collected in May and adopted into families must also be sent home bearing prayers and the observations of events.

* sections noted are excerpts from Peabody Museum web article: “Rainmakers from the Gods, the Ceremonies”

August

SNAKE CEREMONY and the FLUTE CEREMONY are performed by the Snake and Antelope societies in alternate years by two Hopi villages on Second Mesa These are the last of the major ceremonies of summer. The ceremony used to be performed on all 3 mesas.

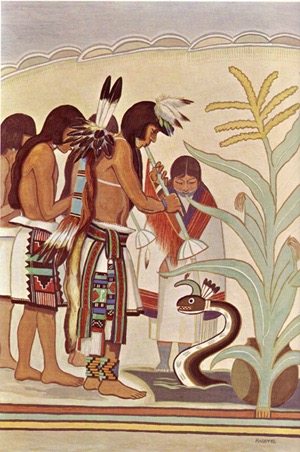

Fred Kabotie historic painting of Hopi flute dancers speaking to the Water Serpent to bring rain

The Flute Ceremony purpose is to help bring the last summer rains to ensure the maturation of the crops. And it is an enactment of mankind’s emergence to this the Fourth World. On the last day, a procession from the springs below with squash, melon and bean vines ascend to the mesa top. Cloud patterns are drawn with white cornmeal and bull roarers twirled to call the rain.

Snake Dance . The snake is a symbol of mother earth and human sexuality from which all life is born. The antelope symbolizes fruitful reproduction and its horns the connection to the higher spiritual powers. Hence the union of the two is symbolic of the creation of life. Antelope and Snake races are held on separate days symbolizing the pathway of this union. Snake priests gather the snakes and keep them in the kiva. In the final phase, the snake priests dance with snakes in their mouth consummating this union. Following this, the snakes are returned back to the desert. This dance is NOT open to non-Indians.

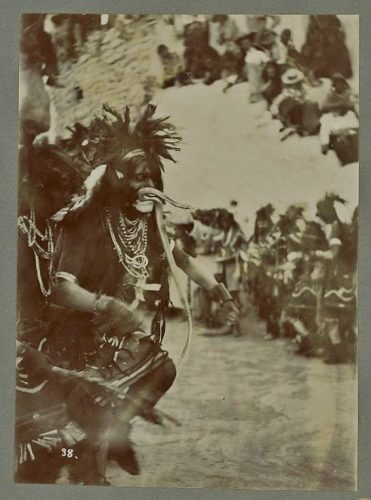

Snake Dance at Walpi, 1900

Butterfly Dance photo by Kyle Knox, traditional farmer and part of the Natwani farming coaltion

BUTTERFLY AND OTHER SOCIAL DANCES such as dances honoring other tribes (Navajo, Havasupai) are also performed. They are joyful non-Kachina celebrations primarily performed by young men and women. They are also a thanksgiving for the blessings of the season.

September

The Hopi ceremonial cycle ends with the three women’s ceremonies celebrating maturity and fruition and sets the stage to begin again with germination.

MARAW Women’s Ceremonials consecrate the harvest season. Initiated adult women participate in the fall ceremonials in the kivas and with public dances.

October

LAKON and OWAQLT–the Women’s Basket Dances are prayers for healthy fertility. The ladies spend several days in a kiva to fast, pray, and chant and prepare.

When the women emerge from the kiva, they chant while presenting baskets to the four directions of the compass, lifting them, then lowering them. Their movements are designed to bring cold, wet weather so that the crops will grow the following spring. Afterward, the women traditionally toss the baskets to the onlookers. These baskets are greatly prized by the men, who will literally tackle each other to obtain one.

October Women’s Basket Dance celebrating harvest and fertility 1940 painting by Hopi artist Fred Kabotie

“..their voices rising out of the depths of an archaic America we have never known, out of immeasurable time, form a fathomless unconscious whose archetypes are as mysterious and incomprehensible to us as the symbols found engravened on the cliff walls of ancient ruins.

What they tell is the story of their Creation and their Emergences from previous worlds, their migrations over this continent, and the meaning of their ceremonies. It is a world-view of life, deeply religious in nature, whose esoteric meaning they have kept inviolate for generations uncounted.

Their existence always has been patterned upon the universal plan of world creation and maintenance, and their progress on the evolutionary Road of Life depends upon the unbroken observance of its laws. In turn, the purpose of their religious ceremonialism is to help maintain the harmony of the universe. It is a mytho-religious system of year-long ceremonies, rituals, dances, songs, recitations, and prayers as complex, abstract and esoteric as any in the world.“

(Frank Waters, Book of the Hopi)Frank Waters (1902-1995), author of Book of the Hopi, is from Colorado—he made Taos, New Mexico his home in the 1940’s.

“With the aid of a translator, Waters related the Hopi view of the world, as told to him by 30 tribal members.

The “Book of the Hopi” took nearly three years to complete. Much of the time Waters lived in harsh conditions on the Hopi Reservation below Pumpkin Seed Point.

In the late ’50s Oswald White Bear Fredericks, a member of the tribe’s Coyote Clan, approached Fredrick Howell, director of the Charles Ulrick and Josephine Bay Foundation, to finance a history of the Hopi people. Eventually Waters was chosen as the writer.

Waters wrote in the opening notes of “Book of the Hopi”: “the Hopi spokesmen willingly and freely gave the information they were qualified to impart by reason of their clan affiliations and ceremonial duties.”

source: Joan Livingston article 10/14/2013